【王晋“娶头骡子”的灵感】在美国举办过展览的中国艺术家王晋,90年代以摄影作品“娶头骡子”成名,灵感来自他八次申请美国家庭团聚签证,均遭拒签,不得不离婚的荒唐经历。

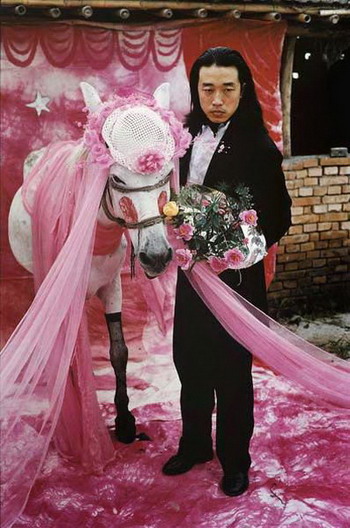

WANG JIN To Marry a Mule, 1995,娶头骡子

艺术界总是在不停寻找新的偶像。上世纪80年代末,中国当代艺术横空出世,来自这个转型国家的艺术家们用其大胆丰富的想象折服了观众。这些作品都带有政治动机,国际买家能够真实的感受到这一点,也觉得这富有异国情调,因为相比之下,西方艺术家的表达显得有些迟缓。在近些年关注中国的媒体推动下,中国当代艺术品市场飞速向前发展,去年的一些拍卖会上,一些中国艺术家的作品拍出了每件200万美元的高价。

中国艺术家王晋解释道,“每一代人都想塑造自己心目中的新中国形象”。他表示,他和艺术同行们发现,在探索“中国的问题及其解决之道方面,”当代艺术是一种有用的语言。王晋的作品正在纽约弗里德曼奔达画廊(Friedman Benda)展览。

上世纪90年代,一些行为艺术家的作品开始崭露头角,王晋就是其中之一。此次在纽约展览的作品,是他自那时起到现在的雕塑和摄影精选之作。

王晋1962年出生于中国北方的山西省,目前居住在北京。他毕业于中国美术学院,曾任教于北京服装学院,直至1992年。

他的成名作是1995年在北京完成的作品“娶头骡子”。在这幅色彩明艳的摄影作品中,身着正装的艺术家紧挨着他的新娘——一头骡子。这一作品在1999年威尼斯双年展(Venice Biennale)上引起了很大的关注。

“娶头骡子”的灵感来自于王晋八次被美国使馆拒签的经历。王晋的妻子在美国求学,他本打算前往美国与之团聚,但屡遭拒签,结果导致两人离婚。在这幅作品中,一头盛装打扮的骡子头戴女士帽,腿穿长筒袜,两颊还抹了腮红,象征着美国官僚机构荒谬地顽固不化。这位“新娘”披着粉红的婚纱,而王晋手拿一束玫瑰。王晋表示,他之所以选择粉红作为这幅作品的主色调,原因在于“再没有人理解红色的含义了”。

在那之前,王晋在他的作品中曾大量使用红色。除了政治意义外,红色在中国传统文化中还有多层含义。它是一种喜庆的颜色,在中国春节和婚礼期间会被广泛使用。

在其1994年的作品“北京—九龙”中,王晋在连接北京和香港的一条铁路上,将200米长的铁轨涂成了大红色。这篇作品创作于中国恢复行使香港主权之前,乃是对“红色”中国的成长,以及收复被西方侵占领土的一种评论。同样,一幅令人印象深刻的照片记录了王晋的另一件行为艺术作品:长发飘飘的王晋将一大箱红色矿物粉猛地抛进著名的红旗渠中。红旗渠是共产主义中国在上世纪60年代的标志性成就。染色的河流象红色血脉一样流淌在山岭之间。

王晋也参与了中国消费主义崛起的浪潮。1996年,他受邀在郑州一个商厦的开业典礼上创作一件作品。他的创意是,在商厦门口彻起一座30米长的冰墙,珠宝、手表和消费品等冻嵌在每一块冰砖里面。开业典礼结束后,被冰墙隔在外面的人群一哄而上,争相撬开冰砖抢走里面的物品。这件作品以一系列黑白色的脸部特写镜头呈现:急切的购物者正猛砍冰砖,搜寻里面的东西。

这件作品让王晋着迷的效果在于,它能让人“看到这些透明物质中无法企及的东西”。

另一件作品“中国之梦”中,三件精致的京剧长袍复制品,它们由PVC透明材料制成,用鱼线刺绣进行装饰。这件作品的主题意在反映飞速发展的科技所带来的后果:塑料等工业迅猛发展,高雅文化付出了代价。作品中,长袍边上还有一组戏剧化的暗光照片,这一次艺术家自己全副武装上阵,成为了不可企及的对象。

近来王晋认定,他“属于幕后”,已避免亲自上场表演。相反,他一直在制作各种人骨的大尺寸陶瓷复制品。两个巨型牙齿和一个下巴的模具占据了此次布展画廊的地板空间。按王晋的说法,牙齿是我们决心获得成功的源泉。

由于这次展览展出了90年代以来王晋的很多作品,有人因此希望,要是能看到他更近期的一些作品就更好了。但此次出展的画廊在纽约上东区一间房子里,那里的空间不足以摆放他最新的雕塑作品——他椎骨的巨型复制物。

作为艺术品市场上的关键成员,画廊承受不起接纳不下王晋这样热门艺术家最新大型作品的代价。画廊必须要满足市场需求,因此,弗里德曼奔达画廊不久将搬迁到切尔西一处较大的地方去。

时间:2007年

翻译:何黎

AN EXUBERANT VISION OF CHINA

The art world is constantly on the lookout for new idols. In the late 1980s it came across Chinese contemporary art and was soon seduced by the strong, unapologetic imagery created by artists from a country in transition. The work had a political motivation that felt both authentic and exotic to international buyers; western artistic expression seemed sluggish by comparison. Helped by the media attention that has been focused on China in recent years, the market for Chinese contemporary art has surged ahead, with works by some artists fetching more than $2m apiece at auction last year.

Wang Jin, whose work is currently on show at Friedman Benda gallery in New York, explains that “every generation wants to create its own image of a new China”. Wang and his artist peers have, he says, found contemporary art a useful language for exploring “China's problems and their possible solutions”.

He is one of a group of performance artists whose work came to prominence in the 1990s and on show here is a selection of sculpture and photography that spans his career from then until the present.

Wang was born in 1962 in the northern province of Shanxi, but has made his home in Beijing. He studied at the Chinese Academy of Fine Arts and taught art at the Beijing Institute of Fashion Design until 1992. He is known for his piece “To Marry a Mule”, which he performed in Beijing in 1995. Vivid photographs of the performance, in which the suit-clad artist poses next to his mule-bride, attracted considerable attention at the Venice Biennale in 1999.

“To Marry a Mule” was inspired by Wang's eight futile attempts to join his wife, who was studying in the US. He was refused a visa each time and the fiasco ended in the couple's divorce. In the performance, a mule, lavishly decked out in hat and stockings, and with rouged cheeks, represents the stubborn absurdity of American bureaucracy. His bride sports a pink veil while Wang clutches a bouquet of roses: he chose pink as the dominant colour for the performance because, he says, “no one understands red any more”.

Until then, Wang had used a lot of red in his performances. The colour has many layers of meaning in Chinese tradition, apart from its political associations; it is a celebratory colour, used widely during Chinese New Year and weddings.

In a photograph of “Beijing – Kowloon” – a 1994 performance that anticipated the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China – the artist painted 200 metres of the railway track linking Beijing and Hong Kong a startling red. It was a comment on both the growth of “red” China and on the country's reacquisition of territory governed by the west. Similarly, a striking photograph documents a performance in which a long-haired Wang zealously flings armfuls of red pigment into the Red Flag Canal, an icon of communist China's development in the 1960s. The dyed canal looks like a red vein pulsing through the landscape.

Wang has also engaged with the rise of consumerism in his country. In 1996, he was invited to make a work for the opening of a department store. His response was a 30m-long wall of ice erected between the shop and the shoppers, with jewellery, watches and consumer goods embedded in each frozen block. After the opening ceremony, the crowd charged towards the wall and set upon it with ice picks. The performance lives on in a series of black-and-white close-ups of the faces of eager shoppers as they hack at the wall in pursuit of consumer collectibles.

The effect of being able to “see through these transparent materials to an object that remains out of reach” is one that intrigues Wang.

The stars of the show are three exquisite replicas of Beijing opera robes, fashioned from transparent PVC and embroidered with fishing thread. Entitled “Dream of China”, they are intended as a comment on the consequences of rapidly advancing technology – industries such as plastics are booming at the expense of high culture. The robes are accompanied by dramatic, back-lit photographs of the artist wearing the outfits: it is the artist himself who has become the unreachable object.

Lately Wang has decided that he “belongs behind the art” and has eschewed performance. Instead he has been making large-scale porcelain replicas of various body parts. Two huge teeth and a mould of his jaw occupy the gallery floor; according to Wang, teeth are the source of our determination to succeed.

With lots of pieces from the 1990s on display here, one wishes that Wang's more recent work was better represented, but the gallery space – an Upper East Side town house – simply does not have room for his latest sculpture, a huge replica of his vertebrae.

As key players in the art market, galleries can't afford not to accommodate these larger works by sought-after artists such as Wang. The gallery must satisfy the market; Friedman Benda will soon be moving to a larger Chelsea space.

扩展阅读

艺术档案 > 人物档案 > 艺术家库 > 国内 > 王晋(Wang Jin)

view.php?tid=3643&cid=28