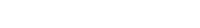

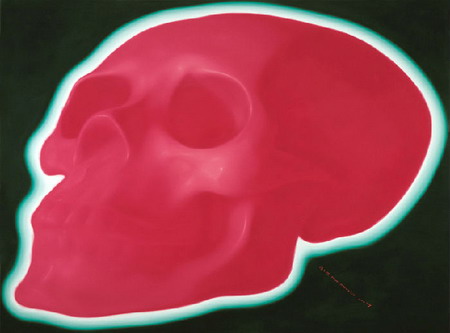

俸正杰作品《生命如花》,布面油画,300x400cm,2007年

其次,中国先锋艺术思想史是一种时间史。一般所说的“时间史”,指人如何认识时间的历史,即人如何把握时间之观念的历史。中国先锋艺术思想史遵循同样的逻辑,其涉及的时间史需要分析艺术家如何表达自己关于时间之过去、现在、未来的意识、观念。

为什么我们把中国先锋艺术思想史的时间史放在仅仅次于语言史的位置?从客观方面言,所有的先锋艺术作品都是在一定的物理时间中发生的,难怪艺术作品除了要标明作者、作品名称、媒介、媒材、尺寸外,必须还要有创作年代。评论家依据创作年代,不仅可以反观艺术家所生存的时代的精神特征,而且可以观察到艺术家如何在具体的一个时间阶段里的生存状态。后者涉及到时间的主观性,涉及到艺术家主观的心理时间,如艺术家在恋爱时期、在生病时期、在亲人离世时期等等就可能会有相应的、不同于往常的创作逻辑的作品问世。俸正杰因着父母亲的去世而创作的《生命如花No.2》(2006-07)以及“意象死生”(2008)的个展便是一例[①]。反之,这些作品本身就内含着艺术家的某种关于生与死的主观的心理时间观念。艺术家不得不面对自己关于时间的经验。同样,他在创作作品过程中会按照一定的逻辑次序安排自己有限的客观的物理时间与主观的心理时间经验;最后,这个创作作品的过程本身乃是作为时间过程(temporal process)而发生的。

宋冬作品《扔石头》,装置,1994-2007

在时间样态上,艺术思想史与艺术文献史的区别,体现在以时间的共时性与历时性为分水岭。作为一种历史性的叙述,艺术思想史当然涉及艺术作品所发生的时间问题,因为没有时间就没有历史,时间中的物理时段是历史得以生存的前提。不过,艺术思想史又侧重于探讨艺术作品所内含的思想,思想的超时间性决定了艺术思想史在某种程度上的超时间性。和艺术文献史相比较,艺术思想史因此更多带有时间的共时性而非历时性的特征。时间的共时性即时间在一个时段里的时间性。除了对于单件作品中的思想展开言说外,中国先锋艺术思想史还将讨论不同艺术家在同一时段中围绕同一主题所呈现出来的作品。在实际的写作中,在一定程度上它也会展开个别艺术家的部分文献史,其目的是为了更好地阐明他在一个相对时段如十年、二十年的创作中内含的连续性的艺术思想逻辑。作为中国当代艺术思想史,笔者在本书中致力于追问当代艺术在艺术家个体那里产生的观念原因,竭力阐明它在当代文化中的特定思想价值。其共时性的时间跨度为1993至2013年。

为什么限定在中国当代艺术这二十年?“当代艺术,在西方指二十世纪六十年代以来的后现代艺术,其主要标志为装置、行为、影像、地景等艺术媒介的出现,其表达对象涉及到人类生活的全部世界图景……在中国,八五新潮美术(以‘中国现代艺术展’为终点、以油画为内容的‘中国广州首届九十年代艺术双年展’为余音),可以说对应于西方十九世纪下半叶的印象主义发端至六十年代的现代艺术时期;从1993年以13位中国艺术家参加的45届威尼斯国际双年展‘东方之路’与‘九十年代的中国美术·中国经验画展’为开端至今的艺术,则类似于西方的当代艺术时期。说两者类似,因为中国的当代艺术,综合了西方的现代与后现代的文化理念,在艺术体制上至今还处于一种前现代的处境。”[②]我姑且称这种现象为“混现代(mixed modern)”。在艺术语言上,八五新潮美术在根本上属于对西方现代艺术与后现代艺术的模仿,虽然在艺术观念上一些作品和中国当时的现实处境相关。不过,中国当代艺术在混杂着前现代、现代、后现代的意义上,我们也可以将其时段回溯到二十世纪八十年代的个别作品上。

隋建国作品《运动的张力》局部,钢结构,钢管,钢球等,2009年于今日美术馆

至于先锋艺术作品中的时间观念,多以现在为中心而不是以过去或未来为中心。所谓以过去为中心的时间观,指把时间中的过去当作时间的起点,它经历现在流向未来。其问题在于过去不断在消逝而无法真正作为时间的起点从现在流走;所谓以未来为中心的时间观,指把时间中的未来当作时间的起点,它经历现在流向过去。其问题在于未来还没有到来而无法真正作为时间的起点而向现在到来。凡是带着这两种观念的作品,其画面都可能表现出一种模糊性的特征,因为作为时间的起点的过去和未来对于艺术家而言都是一种想象之物,因为过去的过去性与未来的未来性使这种想象之物有可能会不清不楚。不过,事实上,过去只有在经历现在中才成为过去,未来只有到达了现在才能够成为未来。因此,就时间存在的现实性而言,现在才是时间的真正起点或中心。在当代艺术家的杂记或言谈中,他们多以具有瞬间性内涵的“当下”来代表这种作为时间之起点的“现在”,尽管前者的瞬间性实际上包含一种相对而言比较长的时段的含义。

[①]同时参见毛旭辉2012年7月母亲去世后创作的《躺着的白色背椅 夏日》。

[②]笔者著:“当代艺术中的受难图像”,刊于《文艺研究》,2009年,第11期,第117页。

History of Ideas in Pioneering Contemporary Chinese Art as a History of Time

Text/ Nishimi Masao Translation by Lance Pursey

As well as a history of language the history of ideas in pioneering contemporary Chinese art is a history of time. What is normally meant by ‘history of time’, is the history of the way in which people perceive time, and naturally, how people use this concept of time. The history of ideas in pioneering contemporary Chinese art follows the same logic. To understand its history of time we need to analyse how artists express and communicate their ideas and awareness of the past, present and future.

That said, in our discussion of the history of ideas in pioneering contemporary Chinese art readers may ask why have we relegated the history of time to merely something second in importance to the history of language? Objectively speaking, all works of pioneering art take place in physical time, which is why when we discuss works of art alongside the title, creator, medium/media, materials, dimensions of a work, we list the time at which the work was produced. Critics refer to this time of creation not only to retrospectively understand the particular characteristics of the time at which the artist was living and working, but also to examine the conditions of an artist’s life at a specific period of time. The latter relates to the subjective nature of time, the psychological time in the mind of an individual artist. After all, for periods of romantic activity, periods of bad health, periods of grief and so on, there are probably works of a corresponding and nuanced nature appearing. Feng Zhengjie’s work “Life like a Flower No.2” (2006-07) and his individual exhibition “Imagery of Death and Life” (2008), both produced following the death of the artist’s parents, are examples of this.(Another example would be Mao Xuhui’s ‘A White Chair Lying Down – Summer Day’ produce following the death of the artist’s mother in July 2012.)Or, conversely, these works contain some ideas of the artist’s views on life and death and his concept of psychological time. In this case the artist couldn’t possibly have avoided dealing with his experiences of temporality. While producing this work he would have had the task of organising his limited supply of both objective physical time and the subjective psychological time, furthermore, the creative process in itself occurs as a temporal process.

The difference between the art’s history of idea and the history of art documentation (a word we use here to encompass not only works of art but also drafts and notes by the artist) manifests in the division between the diachronic and synchronic aspects of time. As a historical narrative, the history of ideas in art is very much concerned with the question of what particular time a work of art was produced, otherwise it would not be considered a history, after all the passage of physical time is what makes up history. However, the history of ideas in art is also largely preoccupied with exploring the ideas contained within works of art. The ability of ideas to extend beyond their time of inception lends the art’s history of ideas its transcendence of the temporal.

When compared with the history of art documentation, we see that the history of ideas in art is more prominently of a diachronic nature than of an synchronic one. The diachronic nature of time can be explained as a kind of temporality, time within a stretch of time. As well as discussing the ideas within a single, individual work of art, the history of ideas in pioneering contemporary Chinese art also discusses many different artists that are working within the same period of time and dealing with a similar theme. When actually writing such a history, there will undoubtedly be reference to the backgrounds and art documentation of individual artists, the goal of such an inclusion would be to better highlight the connective logic of artistic ideas over related periods of ten or twenty years in the artists’ careers.

I will endeavour in this book, as a history of ideas in pioneering contemporary Chinese art, to inquire into the roots of artistic ideas in the minds of the artists as individuals. I will also make efforts to underline the special value of such ideas within the overall milieu of contemporary culture. The scope of this investigation will look at the twenty years of time between 1993 and 2013.

Readers may ask why I choose to restrict myself to these twenty years of Chinese contemporary art. I have stated in previous publications, “Contemporary art, in the west is a term used to describe the postmodern current in art since the 1960s, often epitomised in media such as installation art, performance art, video art, land art, which seek to express human life in its entirety… In China, the ’85 New Wave (with the ‘China/Avant-Garde Exhibition of 1989 as the ending point, and the oil painting exhibition at the 1990s Guangzhou Biennale as an echo), could be seen as similar to the period of art history in the West that was initiated by the Impressionists and stretched from the second half of the 19th century through to the modernist period of the 1960s; while the period of time starting in 1993 which saw 13 Chinese artists took part in 45th Venice Biennale’s ‘A Journey East’ exhibition and the ‘Chinese Art of the 90s: China Experience’ exhibition to now, is more like the contemporary period of Western art. I say the two are similar, because China’s contemporary art has synthesised both the modern and postmodern cultural ideas of the West, however in the sense of system and structure, the art world remains today in a pre-modern state.”( Zha, Changping, “Dangdai Yishu Zhong de Shounan Tuxiang” Images of Suffering in Contemporary Art, in Wenyi Yanjiu Studies of Literature and Art, 11(2009),117.) For now I will refer to such a phenomenon as ‘mixed modern’. The ’85 New Wave, with regard to its artistic language, was at its root an imitation of Western modern and postmodern art. Conceptually however, some works were relevant and linked to the China’s society at that time. Nevertheless, the significance and meaning of this mixing of pre-modern, modern and postmodern ideas in Chinese contemporary art can be traced back to several individual pieces of work that came out of the 1980s.

As for the concept of time in works of pioneering art, the present is mostly emphasised, and the past and future are more overlooked. There are in fact several potential concepts of time. You may have a concept of time focused on the past, where time starts in the past, progresses through the present and moves toward the future. The problem with maintaining this concept is that the past is always disappearing slipping away from the present and unable to truly act as the starting point of time. On the other hand, the concept of time that gives precedence to the future, and sees time starting in the future and passing through the present on its way to the past, is equally problematic. The future has not yet arrived and thus cannot legitimately act as a starting point of time going on to arrive at the present. Any work that contains either of these concepts, probably has a sort of vague or uncertain element to its image, because any work that posits the future or the past as starting points of time for an artist are objects of the imagination. If one attempts to envision an idea of time where the past loses that which makes it the past and the future loses that which makes it the future, the resultant imagery can be very obscure and perplexing. Really though, the past can only become the past by way of the present, the future has to be reached before the present can become the future. Because of this, as far as the real existence of time is concerned, the present is the true origin and centre of time. In the assorted writings and conversations of artists, many use the ephemeral-feeling word ‘now’ (dang xia – which translates as the moment we are in) to express this ‘present’ that is the starting point of time, although this ‘now’ while describing an instant of time actually implies a relatively long passage of time (checked by Zha Changping).

扩展阅读

艺术档案 > 大史记 > 艺术思潮 > 国内 > 查常平:中国先锋艺术思想史引论

view.php?tid=8670&cid=42

艺术档案 > 大史记 > 文献档案 > 中国先锋艺术思想史—— 先锋艺术的定义

view.php?tid=8414&cid=15